This morning, I awoke, pulled on my jeans and overstretched tee shirt, prepared to take Scooter, my anxious schnauzer, for a walk. With the December morning chill, I opened my hall closet door expecting to see a red jacket with a white stocking cap tucked up the sleeve.

Something wasn’t right. I knew it. I felt it. I saw it. The hand of fear gripped my stomach.

In the corner opposite my jacket, a skeleton cocked his head and leaned against the wall with bones chalky white, fully calcified by age. Not believing my eyes, I blinked in horror and forced myself to take a second look. Skeletons weren’t a fantasy to wake up to, nor did I wish to admit I had completely lost my sanity. The calcified bones, shaped in human form, were plain as the new day. Scared spitless, I slammed the door and propped a chair under the door knob. Whatever that thing was, it was not getting out!

For awhile, I avoided passing by the closet. I knew the cliché that every person has a skeleton in his closet, but I never thought anyone sane believed literally the possibility of an actual specter. In spite of the absurdity of it all, I found myself obsessed. Who was it and how did it get in there?

Scooter sat outside the closed door on his haunches, ears perked up, nose twitching. I didn’t know whether he was curious as to what was in the closet or expecting his walk to resume at any moment. After a bit of dog speculation, he gave up and lay with his nose toward the door.

I laughed. How silly. Of course, someone had played a joke and planted a Halloween skeleton to scare me. But the bones looked too real to come from a store. Then I thought someone had arranged with my son-in-law doctor for a cadaver. That idea kept me satisfied the rest of the morning until I admitted to myself that he lived three hundred miles away. Besides, he was the serious type, not one to indulge his in-laws with out-of-season pranks.

I finally settled on the more rational idea I had seen something which was not there—a mirage or a freakish end of a dream when I wasn’t quite awake. I walked past the door once to prove myself logical and in control, and then, passed back again on my way to the kitchen with a handful of day-old dried coffee cups. Barely perceptible, a slight rattle, or maybe a stifled cough, emanated from behind the closed door. Scooter jumped, howled, and pawed the door furiously.

My muscles reacted involuntarily. I jerked the door open.

“Hello Cousin,” he said.

*****

Stunned, I knew I had indeed lost my mind—first seeing and now hearing things.

“What took you so long, Old Woman?” the persistent voice crisp and demanding. “Don’t you remember me?”

“No-o-o.”

I grabbed the knob, but before slamming the door, flesh appeared over the worm pocked bones, followed by long black untrimmed hair, a broad furled forehead, cheekbones landscaped like a turtle shell, dark deeply set eyes that arrested time, a strange chiseled Roman nose slanted slightly off center, and a narrow, pointed jaw. He evolved before me like someone drawing on a sketch pad. Soon broad, muscular shoulders led to a compelling, trim athletic body layered by long johns, soiled breeches, a fringed deer-skin hunting shirt, thick stockings, and scuffed hand-tooled boots with rusted metal buckles. A musket hung from his shoulder and a horn of gun powder protruded from his belt.

“Thought I’d raised so much hell nobody would forget me. I’m Ute.” The voice was pretentious, not too different from a rooster crowing in a harem of hens. Speechless, I stared. With the sound of a voice, Scooter jumped on me, wagging his tail, still hopeful, I suppose, that someone would take him for a walk or give him a bone feast. Eying the bones, his tail wagged faster. “Don’t even think it, these bones aren’t for you.” Absently, I reached down and rubbed his neck.

The skeleton repeated his presence. “Quit ignoring me. Didn’t you hear me?” His angry voice escalated. “Ute Perkins. ”

Registering the reality before me, my mind blurred, eyes refused to focus, and icy legs melted like snow in April. The only Ute Perkins I knew about was a horse thief eight generations ago living in Maryland. Was this him? Hard to believe it possible although at that time, if I had to guess, we’d have been first cousins.

Well aware of the authenticity of Chalkey’s Chronicles and Ute Perkins’ long record of assault and thievery—and seeing his musket—I was not ready to take chances and reached for the door to isolate him from me. I looked him square in the eyes and firmed my voice, “You’re a horse thief. I don’t associate with outlaws.”

“You would if you lived when I did.”

*****

As far as I knew from recorded Maryland history, Ute Perkins was rotten to the core with no mitigating circumstances that would have kept him from his just deserves at the gallows. I couldn’t resist shaming him that he had come from an illustrious family and was the blackest of all black sheep.

“Your mother was a Sherrill, your grandfather—the famous Conestoga Fur Trader—opened up the Pennsylvania and Virginia frontiers, and your Uncle Adam was the first white man to cross the Catawba River in North Carolina.”

“Why you bringing up those Sherrills? I’m a Perkins.”

“Your Ma was a Sherrill.”

“So what? She wasn’t exactly a gilded lily of the fields, you know.”

“You’re dodging the issue. You know as well as I our kin were respected Indian fighters , militia captains, doctors, preachers, and notable politicians; even one the wife of the first Governor of the State of Tennessee. You can’t have forgotten what happened at Kings Mountain when our Patriot kin mopped up the British.”

“Now you’re preaching. Can’t stand holier-than-thou hypocrites, especially if their last name is Sherrill.”

Ute had pushed my hot buttons. I was getting nowhere, but I still had a full head of righteous steam to lay on him. “Your brother was a Perkins. Gentleman John with his ten thousand acres, was once the largest land owner in North Carolina and world famous for his Perkins’ Red Apples and all those thoroughbred racehorses.”

“Lay off, Cousin. Relatives don’t mean shit. Lay off.”

Looking at the scoundrel with as much disgust as I could muster, I felt a collision of wills coming on. I wouldn’t give his brazen attitude any satisfaction. I lobbed a volley right in his face. “How could you disgrace yourself to sink so low as to become a common horse thief?”

Ute didn’t drop his head in shame nor show any recognition of guilt or remorse. He belligerently jutted his jaw forward in sharp contrast to the sunken eyes and emaciated cheeks I’d seen before. A wild and feverish fire flamed in his eyes.

“All fine and good, Cousin, but you’re talking after the fact, not while I was living. Since you’ve conveniently forgot the other Sherrill and Perkins scoundrels, I guess now is as good a time as any to tell you how it was.” Clearly, well practiced in his defense, he was bent on manifesting his circumstances in the best possible light.

His throat obviously dry and not used to talking, he coughed and rubbed his nose as if it might drip. He reached and stroked his throat. His contorted face made my stomach weak. He painted himself the very picture of imminent suffering.

Alarmed he might collapse, I forgot I was talking to a skeleton. “Are you all right?”

He shook his head and gagged to vomit, but not even spittle was present. His voice scratched like chalk on a board. “Can’t you see? I’m bone dry and starved. Posse wouldn’t give me anything to eat or drink before stringing me up.” He spoke as if the event happened yesterday. “If not too much to ask, would you have vittles and ale? I’ve been dreaming of back strap venison in gravy and a barrel of ale.”

“Sorry, no venison. Times have changed. A hot dog and long neck will have to do.”

Ute eyes bulged with horror. “Don’t want nothing with dog meat in it—that’s disgusting. Any fool knows no one cooks necks.”

Obviously a dark matter indeed for him to consider, his face reddened. “Is that all you have?” He scratched his inner thigh, and leaned forward. I thought had he eaten breakfast, he would vomit again.

“Too complicated to explain.” I said simply, “Hot dogs are cow’s meat in a gut, and a Lone Star long neck is beer in a bottle.”

“Beer? The same as ale?” He grinned like a child, happy, his dry tongue licking flaked lips. “Now that’s more to my liking.”

Even speaking a few words agonized him. He clinched his throat and gasped with a spasm so deep I feared his brittle bones would break. I hurried to the fridge, popped the cap with my thumb, and set a Lone Star in front of him. After his first hurried gulp, he tipped the bottle and emptied it without stopping. He wiped his mouth with his sleeve and demanded, “Bring me another.”

After his third, his discomfort eased, and he began to talk.

“First off, you have to understand, Cousin, I was born a thief, never knew anything different.” He wanted me to think he was a chip off the block as his father had been, and his father before him. I knew of his grandfather. William Sherewell smuggled sotweed in England and reived cattle and horses along the Scottish borders, but in no way could Ute claim he’d been thrust from his Ma’s womb a thief.

I zig-zagged the hot dog with mustard like an Oscar Mayer ad and put it in front of him. He paused at the sight and turned it to examine all sides. He put his nose down to sniff, and poked it with his forefinger. When it didn’t jump at him, he hesitantly took a bite, his mouth puckering like eating a sour pickle. The scowl on his face told me he’d rather have tasted a skinned skunk. “Don’t know what animal this is,” he pointed to what he must have thought was a turd excreting yellow bile, “but it don’t seem to have felt well.” He gingerly put it back on the plate, evidently preferring to talk.

“Guess my memory goes back to one morning when I was five and hungry as I am now.” He counted the years on thinly covered bony fingers separated by protruding scarred knuckles. “Must have been 1734 while we were living in the backwoods of St. Mark’s Parish.”

I raised my brow, a question of geography forming in my mind.

“That was Maryland,” he patronized my ignorance.

“Thought so.” He had me on that one. I mumbled, “Forgot parishes were in Maryland.”

“Ain’t the only thing you’ve forgotten. You want to know my story or not?”

I nodded.

“I was dirty and hungry—hadn’t eaten since day before. Equally filthy, us six clamored for breakfast trying to shove past sister Elizabeth, the oldest and in charge, who was filling an ale bottle half full, the last of the milk from the morning’s pail. Banging us away with her hips, she pushed the hog-gut nipple into Johnny’s mouth with one hand and waved her other arm for us to stay back. Johnny’s the one you called Gentleman John.

“To start with, there weren’t any biscuits left when I reached the table.”

I nodded. More than merely telling me his story, he had transported himself back to Virginia to the kitchen table with his brothers and sisters.

“This particular morning, I could no longer stand the ache in my stomach. I jumped from the chair, kicked Elizabeth hard, butted my head against her with all my might, grabbed her arm and yanked the bottle.”

“Uttie, let go of me,” Elizabeth shouted, lifting the milk high out of reach. “This is for Johnny. Shame on you. He’s a baby.”

“I screamed a tantrum and pounded harder with my fists until she dropped the bottle. I scooped it up and ran outside to the porch before she caught me.”

“You stole milk from a baby? Your own brother?” I was aghast.

“That’s how I got breakfast—taking what I could and gobbling it down before my older brother did the same to me.

“After she laid on her whipping, I remember her in tears complaining to Elisha, who at thirteen was responsible for the barn and fields, ‘What can I do? Ain’t milk and biscuits for all of us. Ma was supposed to bring flour and potatoes. She ain’t home yet.’

“Done all we can. Down to one cow and she’s about dry, and chickens ain’t layin,” Elisha responded. “And you know when Ma comes, she’ll be sick and forgotten us.

“I knew about sore throats, coughs, and fevers. I had plenty of them, but didn’t know what caused Ma’s sickness. Whatever it was, it was bad. She went directly to bed every time she came home. I was seven before I learned from Elisha that Ma’s sickness was of her own making from the tavern. I knew then she didn’t love us.

“Elizabeth was our extra Ma. She put out in the morning biscuits, eggs, and milk, if we had any, to feed us for an entire day. If you didn’t get to the table first you went without. She took us to the creek once a month to take our clothes off and wash up, sewed the rips in our overalls the best she could, and tried to keep the cabin swept. I barely knew Pa. He, like Ma, was usually gone. Elisha said he was out roaming Spotsylvania looking for horses and land. Before Ma got big with Johnny, we hadn’t seen Pa for more than two years, so this time if I was to know the truth, he was most likely in jail.”

As appalled as I was, Ute was wrong to use his Ma and Pa for his own excuse. “But that was them . . . doesn’t account a whit for you. Even more so, you should have learned from your Pa and Ma and known better.”

“Seems to me, Cousin, you’re throwing stones and not listening.” He poked at the cold hot dog. “I’m starving. Ain’t you got vittles better than sick dog meat?”

Scooter whined at the insult, tucked his tail between his legs, and jumped to the safety of his favorite chair. He was finished socializing.

“How many times do I have to tell you it’s cow’s meat? Don’t know how you figure it’s my obligation to feed you. Seems like you’re doing more complaining than appreciating. Your brothers and sisters didn’t end up thieves. Don’t want to hear more excuses.”

“Oh, don’tcha now,” his eyes took on a glimmer, one of an unwillingness to let stand she thought him a loser.

But I saw what I saw. A thief. No way could I get beyond the judgment I’d already formed.

“You too uppity to learn the truth?” he challenged. “Since you got me started, I think I’ll tell you anyhow.” Intoxicated with the sound of his own words, the braggart continued. “Don’t rightly see what you can do with me since you know I’m here. Already froze my ass in purgatory, pitched below by the devil’s fork, and burned in hell. No lie in that. Devil says I’m your skeleton and he put me in your closet.”

“But I was looking for my jacket, not you.”

“True, but now, old woman, you’re responsible for me. I’m doomed to be a permanent resident in your closet and won’t have peace until you let me out. I see that ain’t happening unless you change your attitude and hear what I have to say.”

“Ain’t for you to tell me what I want to hear and what I don’t,” I shot back. “No way am I responsible for anything that has to do with you. Besides I haven’t decided if I’d dare tell anyone about any skeleton in my closet. Particularly you. You aren’t exactly acceptable conversation for me and my friends.”

“Don’t pick on me. Your nose is so high in the clouds no closet skeleton would be acceptable. I’m only telling my story. After all, you asked why I became a thief.”

My ears ached. Plainly this skeleton could argue all night. I heaved a sigh. “If you must, go on.”

“Pa started me wrong.”

There he went again, blaming others. “You mean, like father, like son. That cliché is older than the hills and stupid.”

“Think what you must, but when I neared ten, I started hearing rumors from Elizabeth and Elisha talking, especially about Pa . First the sheriff caught him with John Baldwin’s horse in Ann Arundell County. Then he stole a gray horse from the widow MacNemarra of Annapolis and the judge sentenced him to pillory for one hour, and to the whipping post for twenty five lashes. Grandma Belcher went to court with him pleading that since he swore himself innocent, he didn’t think he’d need proper counsel.”

“Sounds like jail time to me,” I interrupted.

“Not at first. With Grandma Belcher being of good name, the judge cancelled the pillory but arrested Pa for the Baldwin horse. He landed in jail. After that he had more accusations thrown against him than Elizabeth and Elisha could keep track of: indictments for trespassing, assault and battery on both men and women, more horse thieving. Pages and pages of servant complaints. You name it. He was guilty. The sheriff rode so frequently onto our place looking for him that Elisha carped we might as well had a stall in our barn with his horse’s name on it.

“When Pa wasn’t in jail and it suited him to come home, he prided himself an upstanding citizen. Served on juries, awarded numerous bounties for wolf heads, bought and sold land, and recorded several deeds in his own name. Also, counting back the months we were born, we pretty well figured the occasions when he was home.”

As Ute recounted his Pa’s vicissitudes, I found his story partly despicable, partly disgusting, and partly ridiculous. Although not entirely agreeable, I began to gather interest, like reading a wild-west book, and having wasted the time to read past page eighty nine, forcing myself to finish it.

With his aversion to hot dogs, I began to think about defrosting and frying Ute and Scooter a hamburger. But my pity didn’t go so far as to let him out. He’d have to eat in the closet.

I whistled, and Scooter followed me to the kitchen willing to substitute meat in his bowl for a walk. I called back to Ute, “What about your Ma? How’d she get hooked up with a loser like your Pa?”

With only me and Scooter in the house and the TV off, I heard his answer plain enough.

“At fifteen Ma met Elisha Perkins and ran away. Uncle Adam went looking for her, but found them already married by a minister in St. Mark’s Parish. This was before Pa roamed the countryside. Elizabeth, Elisha Jr., and Margaret were born one, two, and three as quick as three foxes jumping a fence during a hunt. Elizabeth says the first time she remembers seeing the law was when a constable rode to our cabin when she was four. Pa had failed to register his marriage to Ma nor any births. He didn’t have money for the fine and skedaddled. After that, he made sure he was never home when the law came.

“With Pa gone so much, Ma was lonely and drank Pa’s whiskey during the day and cried herself to sleep at night. On rare occasions when he was home, they both got drunk and argued until one would accuse the other of fornication naming almost every man and woman, married or not, in the Parish as bed partners. When Ma shrieked, ‘adulterer,’ Pa hit her across the mouth. “So you want my ass, I’ll give you one to remember.” Then twisting her arm, he hauled her off to bed.

“Us children in the loft listened to the racket below afraid one would kill the other. When Pa threw her into bed, the noise got worse. They’d moan, shake the bed, shout obscenities, and then when the moans stopped, call each other Darling and Sweetheart. In the morning, when Pa put his arm around Ma, she’d ask, “How is my bull today?” He’d answer, “How is my cow, this fine morning?” And then they would laugh and kiss—all in front of us.”

Ute didn’t pause over the vulgarity of what they’d said, but I had never heard such talk. These were relatives I wouldn’t own up to under any circumstances. They could stay in someone else’s closet!

As if he’d been thinking and not spoken aloud, Ute ignored my disgust and gazed upward gathering his thoughts before continuing.

“Within days, Pa was gone again. Each time he came home, the same thing happened. I’d had my fill and could no longer live in the house with them. When I absolutely had to come home, I fixed a place in the barn to hide my whiskey jug, smoke my tobacco, and sleep.”

“And how old were you?”

“Maybe twelve.” Ute twisted his fingers, his voice muted expecting me to understand without understanding. Suddenly burying his thoughts, with me mortified and him stressed out, a silence ensued, his face white as powdered snow.

Obviously, thoughts of his family stirred his mind. I saw sadness form in his eyes. Maybe I’d beleaguered him enough. I began to look at him like a wounded boy. “Ain’t saying you can go outside, but you can sit at the kitchen table with Scooter while I fix hamburgers. Do you like onion, tomatoes, and lettuce on your bread or just meat?”

“Lettuce is weeds for goats. Didn’t have tomatoes, if you mean those red things. Don’t understand at all what you call vittles. Since you don’t have venison, I’d like pole beans cooked in bacon and sweet potatoes smothered with maple syrup. If you have fresh churned butter, corn on the cob would be nice. I swear you meant to poison me with that hot dog, and now this thing-a-ma-jig hamburger?”

“I think a guest, even if a horse thief, ought to eat what I prepare. I’m fixin a hamburger and that’s it.”

“Don’t get huffy. Get me another ale.”

“You’ve had the last of my six-pack. Don’t have any more in the fridge that’s cold.”

“I’ll drink it warm.”

“Warm beer?” I made a face.

With Scooter tripping under my feet like he does for his walk, I opened the outside door and fetched another six pack from the garage. I slammed it down in front of him. “Drink it anyway you want. It’s your poison.”

“How was I to get cold ale in the backwoods?” he smarted as if I was an idiot. “Always drank it warm.” He took his time with a bottle and was embarrassed he couldn’t flip off the crinkled cap. I easily popped it for him and brought a tall mug from the cabinet pointing for him to pour. When foam reached the top, he started talking again. “Suppose you want to know more about Ma.”

“More excuses?” I challenged.

“If you’re going to be nasty, I’ll eat your hamburger, but don’t tell me it’s good as venison.”

The chump! He acted like he was doing me a favor. “Might consider that if you tried, you’d find it quite pleasant to eat.” My temper showed. I wanted to churn his hamburger down the garbage disposal.

Nothing bothered him. Being free of the cramped closet, he stretched his legs, straightened his back, and flexed his shoulders. He called, failing pitifully to fake good manners, “Didn’t mean to hurt your feelings.”

He shifted his body and turned his chair to face me, his voice slurring, his eyes moving from side to side watching me closely. After a minute, he peered upward again as if a fly speckled the ceiling, and ran his hands across his temples. It was though his next thoughts lurked just outside of his memory or what was coming next was something he’d rather not talk about. His tone became acerbic and his long-harbored bitterness surfaced.

“I guess when Pa couldn’t stand coming home any more to a drunk, he kept away longer. Ma, in retaliation, took to staying at the tavern. Rumors of her carousing got serious. Somehow—I wasn’t the one who tattled on her—Pa heard about a Christopher Holmes and got the idea he and Ma were living together at his place in Orange County.

“Pa cornered us and under threat of a whipping, we confessed Ma was gone as much as he was. When his spies saw the bastard Holmes and Ma leaving the tavern together arm in arm late one night, Pa became convinced she was bringing shame upon him. He brought suit for adultery and the case went to the Grand Jury. Uncle Adam came to help defend Ma but the Grand Jury did find that a Christoper Homes doth live in adultery with wife of Elisha Perkins in St. Mark’s Parish.

“Ma went crazy and testified she’d never married Pa and couldn’t possibly be guilty of adultery if they weren’t married. Furious, she issued a counter suit of assault and battery. The Constable brought Pa into court accused of being a barbarian and using his wife Margery. At Uncle Adam’s insistence, she asked for separate alimony. Pa countered, and the Grand Jury agreed if she wasn’t married to him, as she claimed she wasn’t, he couldn’t be legally forced to pay alimony. The judge dismissed Ma’s case.

“Pa got the assault and battery case against him continued indefinitely. The Judge extended his case against Christopher Holmes as an adulterer. Ma came home but didn’t have sense enough to stay sober. She went back to live with Christopher Holmes but soon ran off to Spotsylvania going door to door wailing she still loved Pa, and demanding to know where he was.”

“Didn’t that cause more trouble?” Strange, in spite of what his Ma had done, I felt his Pa was as guilty as she and the court had railroaded her. Although I wasn’t yet ready to take up her cause, I was fixated and wanted to hear the rest of the story.

“Well, I can tell you the good citizens of Spotsylvania saw Ma a fallen woman and complained she was a common disturber of the peace and insisted she be brought before the Court.”

“A fallen woman? Her husband was a thief, for goodness sakes! An abuser.” I took exception to the gossips’ name calling and gave Ute a sharp look.

“Don’t look at me like that. It wasn’t me who called her that. Even a fellow like me cares something about his ma even if there weren’t much to admire.”

“And your Pa? I suppose you found much to admire about him?” I countered, a confrontation on his bias of men’s supremacy over women imminent on the tip of my tongue.

“Ain’t dumb enough to argue that with you. I was telling you at this point there were two cases—one for adultery and one for disturbing the peace. I can quote exactly what happened when the Grand Jury announced the verdict on the adultery issue.”

“Christopher Holmes, defendant to answer, committing fornication with Margery Sherrill Perkins, case dismissed.”

I groaned. After all it took two to fornicate. Without complaining to Ute about the obvious injustice which he preferred not to see, I went to the stove and angrily flipped the hamburgers. He paid no notice to my disgust, and continued talking.

“After lunch, the Grand Jury met again, finding Ma guilty of being a common disturber of the peace. The judge sentenced her to jail for one year and a day. Ma collapsed and the bailiff hastened to fan her face with his hat to rouse her.

Uncle Adam and Grandpa Sherrill were furious. With Pa free from paying alimony and Christopher Holmes free of adultery, they watched Ma, sobbing for the fate of us children, led away to jail in chains.”

“You mean only your Ma got punished?” I found myself livid—both men off Scot free. The final straw of iniquity. “Not fair, not fair at all.”

Ute shrugged and retorted, “Grandpa and Uncle Adam were on Ma’s side and sat in court. She didn’t deserve to expect more.”

“Maybe so. But it sounds like they did very little.”

“You’re wrong. Stood by her and didn’t give up. It was Uncle Adam who convinced the sheriff to set Ma free three months later when he learned she was pregnant and I was soon to have a half-brother.”

*****

“Seems to me you’re plenty loose talking about your Pa and Ma, but that doesn’t excuse you. Give me some credit. You may be clever, but not that clever. You chose to be a horse thief and you know it.”

“Suppose I did. Don’t give you no call to judge me. I want out of here as bad as you want rid of me. Trapped in your closet isn’t my choice. After what I’ve told you, anyone intelligent would know exactly why I am a thief.”

My voice turned syrupy sweet. “Well, do humor me if I’m too dumb to believe your lies.”

“Hell, they ain’t lies. If you go back to Augusta County records book, and Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, there’s plenty to prove my story.”

He smirked, jabbed his puffed up chest, and boasted, “You’re looking at the head of the notorious Perkins gang they write about. Known all over Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina. The fool sheriffs thought we were four gangs, since like Pa, I used whatever name came to mind—John Bland, John Anderson and James Anderson. Actually, the gang was only me, Jesse Jackson, David Frame, John Botkin, and George Steele. We stole saddles, horses, and once in a while a slave or two. We scared the bejaysus out of everyone.”

I recognized if I let Ute start on his own story tonight, nothing would stop him. “Enough,” I interrupted. “No more. I’m shutting the door, and you’re staying in the closet. No argument.”

Exhausted, I intended to go to bed early, but decided to take a minute or two and check my computer to see what was available on the search engines. What I found took the next three hours to decipher.

John Bland (alias Uttie Perkins) committed to Philadelphia Gaol on suspicion of stealing two horses and a Negro boy named Peter, age about 10, from one Gistin, living at Poff Pon, South Carolina. I knew it hadn’t bothered him that he’d confessed he was actually Ute Perkins since he’d of been more proud of his escape from Nicholas Scull, the Sheriff of Philadelphia County.

As James Anderson, he was charged by William Robertson and indicted for an incident that started as a trespass but ended when he poisoned Robertson’s fowl and hogs with ratsbane. Had something nefarious to do with his wife (whom I didn’t yet know about) owing debts.

The records listed numerous times he’d been bound over to keep the peace. From Wikipedia, binding over meant he’d been involved in some kind of violence and the courts were threatening him with jail if he broke bond. The charges included incidents with Roy Russell, Jess Watterson, Thomas Miller, John Erwin, John Burnsides and a host of others. I quit listing them after one particularly nasty one for stealing property from Thomas Pleasants.

To my surprise in 1747, he married Elizabeth Skeleron, widow of William Skeleron of Augusta County, Virginia. Although wed by Reverend John Hindman, who held his services in a court house, they hadn’t bothered to get a license. Later in 1756 when caught stealing, she denied the marriage although calling herself “Elizabeth Perkins.” I thought, déjà vu—same illogical denial his Ma used to avert guilt.

At this point I was stymied as to what was next. Had to know more about Elizabeth Skeleron and brewed a cup of coffee as a companion to my digging, now stretching long into the night.

On a number of occasions, both of them were bound over for peace in one scrape or another. I immediately thought them an eighteenth century Bonnie and Clyde.

I swear I didn’t fall asleep at the keyboard, but the next thing I knew, Elizabeth married James Anderson the same year she married Ute. I tut-tutted. That must have been the scalding scandal of the day.

Putting two and two together, I guessed they needed a new name and were both thieves traveling incognito so sheriffs wouldn’t recognize their new name “Anderson” in order for them to dodge the “Perkins” warrants held against them. Hmmm. More confusion. Four different gangs and two different marriages. Three states. All of a sudden, I wasn’t absolutely sure who I had in my closet.

By two o’clock in the morning, and many more warrants and stolen horses later, my head ached. I felt I knew enough to boil Ute in his own kettle of fish. I fell asleep nagged with the odd feeling that nowhere did I find reference he’d been sentenced to the gallows and hung.

*****

It didn’t seem morning yet, but Ute thumped and banged in the closet loud enough to wake the whole neighborhood. The dog across the street barked. It was if Ute spent the night thinking up more excuses. I could see why the saints buried in the cemetery in Augusta County might have complained and kicked him out.

Squinting my eyes to the clock, I wanted to thump and bang him. It was five o’clock and even Scooter was still asleep in his crate. Reluctantly, I got out of bed and opened the closet door to tell him to shut up and let me sleep in peace.

There he was squatted behind stored TV trays, my umbrella sprung open. My white stocking hat was on his head, and he’d tied a yellow silk scarf around his neck. A pile of coat hangers lay tangled on the floor.

“What’s this mess? Now I know why you were so noisy.”

“Don’t just stand there.” He struggled with the umbrella. “Help me get this damn thing closed. Thought I could trust you, but when were you planning to hang me with those?” He pointed to the hangers on the floor.

“Serves you right. Should have left my things alone. Pity you can’t stay away from trouble.”

“Not so, Cousin. My troubles were Uncle Adam’s fault. If he’d taken me with him when he rescued my brothers and sisters while Ma was in jail, I would have turned out different.”

I could see no one had changed the broken record on his phonograph since I’d shut him up last night. He was still blaming everyone else. “Don’t know how you figure you were your Uncle’s fault—you were thieving way before your Ma went to jail.”

“Yeh, but he didn’t help me when I went to him.”

“You went to him? When?”

“I had a traitor in my gang and didn’t know it. Supposedly, John Harrison got caught stealing chickens and let the sheriff talk him into a plot against me. John stole a horse and saddle from me and turned them into the Sheriff saying I stole them from Joseph Powell. The Sheriff took the horse and saddle as evidence and swore out a warrant for me. Terrible timing because me and the rest of the gang were running from John’s pa, who was after the reward offered for my capture because one of my gang was accused of killing two persons. Not chickens at all—it was all cooked up. I saw right away what John and his pa were up to. They didn’t care a lick that I hadn’t condoned any killing.”

“Sounds serious. What happened?”

“What do you expect happened? They caught us. Never did have good luck. John Harrison knew where we were hiding. Wasn’t my fault. We were set up.

“As it were, Patrick Finley was out scouting the horses on Peter Scholl’s place when the Sheriff apprehended us. When he got back and found us gone, he figured we were in jail and waited until nighttime to rescue us. While John Bodkin shot up the saloon in front of the jail, Patrick sprung me and George Steele out the back. We scattered so the Sheriff wouldn’t know which escape trails to follow.

“I rode as fast as I could to Uncle Adam’s place. Couldn’t go to Pa’s. He was living with his new lady friend and didn’t want me around.” His boisterous voice turned wimpy, his lower lip quivered, as if he were the last orphan on earth. His muddled words trickled out. “Had nowhere else to go.

“Uncle was none too happy I got him up in the middle of the night and wouldn’t let me inside his house. Said he don’t want someone like me near his children. Auntie Elizabeth got all huffed up and told him to tie me in the smoke house until morning when he could ride to the Sheriff’s to turn me in.

“He shouldn’t have done that. I was kin, as much as my brothers and sisters he’d taken in as family. I never believed I’d ever see justice until I heard shortly the Sheriff and a posse come upon Uncle Adam and accuse him of harboring a horse thief and murderer. They didn’t listen to him when he claimed he intended to turn me in when the sun come up. They found me in the smoke house, and I stayed mum. Wasn’t going to let Uncle Adam off the hook since he showed no intention of helping me.”

As quick as a rat scampering down his hole, Ute’s memory turned euphoric. “It was justice, all right. Pure, glorious justice. Almost ridiculously beautiful, seeing Uncle, a pristine Sherrill, under arrest. He was fined one thousand dollars and Grandpa had to post bond assuring Uncle Adam wouldn’t commit any offense against the peace for a year and a day.

“Course I didn’t stay in jail long . . ..”

“Time out,” I called. “Stop rattling your mouth. I haven’t had coffee yet and Scooter needs his walk or his pipes will burst.”

“Take your time. I need a nap.” He rubbed his eyes. “Got no sleep last night. I’m dead tired.”

****

When I returned with Scooter, I observed only a skeleton in the closet slumped over as I had first found him. Evidently, sleep reverted him back to a bare-bones skeleton. Although the bones in his chest rattled a faint snore, I wasn’t sure if his new condition was permanent or if he’d wake up and return to the specter I’d been talking to.

Thinking back over our conversations, I thought it funny he first thought of one thing, and then another, and then the third thing returning to the first. I wondered where his mind would be if he awoke. A spectacular escape? Caught again? Hanging? Did his life end on a tree branch or from a scaffold?

As if his battery had run down, the rattle in his chest stopped. I couldn’t avert my eyes from looking at the spent structure of bones before me. Lying there in the arms of nobody, he was so helpless. I caught myself questioning if we’d even talked, if his stories had been nonsense, a fabrication from years of living in some other body, some other time, and rejoicing when he found a patsy to believe the unbelievable.

Befuddled, I wondered whether Ute was a pool of my own imagination that I had fallen into. Perhaps I was fascinated with having a horse thief skeleton in my closet—an apparition no more cogent than the difference between being caught in a windy rain or a rainy wind.

I questioned last night’s lack of proof in the records that Ute died hanging. In telling his story earlier, he left little doubt the posse strung him up. Had he hung until dead or had he escaped? If he somehow got away, what eventually happened?

In my mind, his greatest sin was his hatred for the Sherrills, his Ma most of all. Perhaps as a child when he needed her the most, she’d let him down the hardest, or that the Sherrills were everything he wanted to be, but never was.

I stiffened my upper lip—now was no time to invent excuses for him. With my head logical again, I saw empty beer bottles on the kitchen table and the skillet where I’d fixed the hamburgers. A half-eaten hamburger lay to the side. The truth could be no clearer than that.

It was time to close the book on Ute Perkins. To me, if he never awoke, he would remain a skeleton in my closet, just plain rotten, never to be redeemed.

Was I wrong?

I read the Virginia archives again. I’d missed the last line of the last page. Ute Perkins died in 1814 in Augusta, Virginia, at the age of eighty-five.

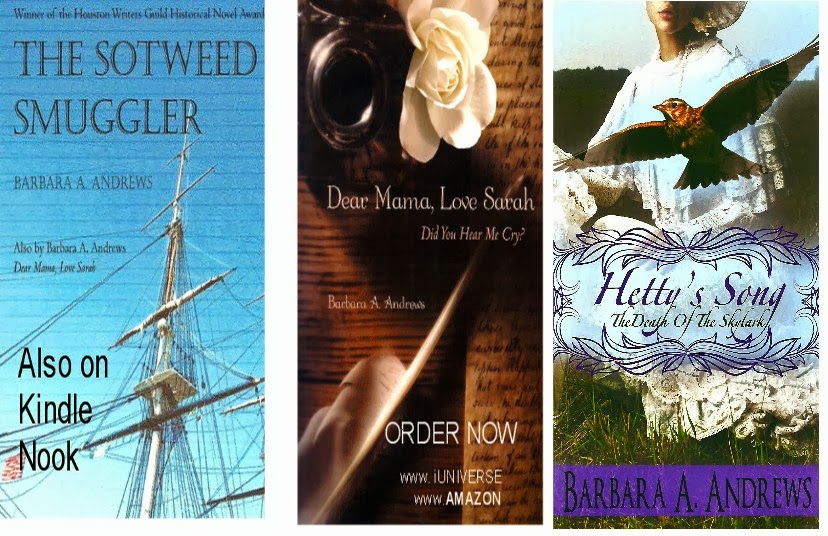

Ready to Read

Historical Novels -Bobi Andrews

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Saturday, August 18, 2012

LIBERTY BILL, THE BUFFALO

Preface

You’d have to know Liberty Bill to appreciate this fine beast of the prairie. You’re reading correctly. Not the Liberty Bell hanging in Philadelphia that made America possible. Not Buffalo Bill the famous wild west performer, although both had much in common. Each was a product of Iowa during the buffalo rage roaring through the prairies west of the Mississippi River during the early 1800’s.

In Liberty Township, Clarke County, Iowa, circa 1844, a certain buffalo calf was as famous as the world renown performer, Buffalo Bill, who was touring Europe and meeting the Queen of England with his crowd pleasing theatrics and tall stories of escapades in America’s wild west. Not to be outdone, the unique talents of this eccentric buffalo celebrity were published in the Clarke County Osceola Sentinel, the local newspaper. He was revered by the local population as evidenced by a thirty-five-year old, dog-eared clipping saved by Mrs. George Evans of Woodburn, Iowa, published through USGENWEB, Clarke County, Iowa.

Although hard to prove with thousands, more likely hundreds of thousands, of buffalo roaming the tall grass and deep rooted turf of the prairie, Liberty Bill of this story may have been related to the young bison John Holt trained as a “plow horse.” When the Holt family had no oxen and faced disaster with no way to prepare for crops, John improvised with a young buffalo calf he’d captured and one of his frontier-hardy steers to pull the plow that “turned the soil.” I will let you pause a moment for your imagination to be a frontiersman on a horse riding past the Holt farmstead. Right before your eyes, you’d see the anomalous spectacle of John behind the plow pulled by his truly, the deft buffalo yoked to a wary steer. Snorting displeasure and pulling on his traces, the latter was obviously deeply conflicted about his partner in labor and his own degraded station in life.

I’ll even wait while you take a second look.

For the purpose of honoring ancestral privacy of innocent descendents in the telling of a historical story laced with fiction, we will assume Liberty Bill was the property of an anonymous Jim Henry Hunt, who lived with his family as neighbors to the fearless Kilmore, adventuresome Windriff, and patriotic Bakker families. I anticipate true kin will recognize the families who inspired this story.

It may have happened like this.

While envious waggers might say his extraordinary patience was a gift, it was no gift at all—he’d come by it the hard way. From the moment he emerged from his mother’s womb after a long, difficult labor, life had been a struggle. With the slightest movement agitating his arms and legs, his breathing became difficult and his heart beat irregular—first thrashing furiously and then hardly at all. Each day, his life was a shaft of wheat floating precariously in the wind.

Surviving a difficult childbirth, Celia vowed not to lose the baby she and God had worked so hard to bring to life. Night and day, she suckled him at his first whimper and protected him when his brothers and sisters might accidentally bump his cradle or rouse him with unnecessary noise. So immersed in her mission, Celia delegated his sister, Elizabeth, to take over the running of the household.

Miraculously, by age six, Jim Henry's breathing became normal and only rarely did his heart race beyond control. After months of begging his mother, and his father’s insistence that he no longer needed her eagle eyes hawking his every move, he finally was allowed to play alone in the barn. Excused from strenuous farm labor, but not without sibling resentment towards his soft, protected life, he watched his father and older brothers struggle nearby to clear pastures from trees, stumps, and occasionally limestone outcroppings prevalent in the rolling hills of Martin County, Indiana.

Later, Chester, a German shepherd, came along, a gift to the older boys from Uncle Drury, whose bitch birthed five puppies. Celia feared the puppy would bring too much excitement for her fragile son, but acquiesced when Jim Henry calmly took on the assignment of methodically teaching the frisky Chester to sit, lay, and fetch a stick. Although belonging to Jim Henry's brothers, Chester frequently preferred lying peacefully in the barn while his companion rubbed a certain spot behind his ear. Talking back and forth as boys and dogs often do, the two of them watched the ants go about their work.

One evening late in July, his father barged into the kitchen, sweat dripping from his brow, an ear of corn covered with deadly black smut in his hand. He ranted, “Look at this. Third year corn’s ruined. We’ll starve. I tell you, Celia, we’ll starve.”

Turning away from his wife and eight children who still lived at home, and who were seated around the kitchen table anticipating supper, he sat morose, head in his hands, not responding to anyone.

Celia consoled, “Not your fault. We’ll get by somehow. Is there anything I can do?”

“Don’t see how we’re going to make it,” he muttered.

“What are others doing—their corn has smut, too.”

“Some are talking Iowa.”

“Why Iowa?”

“It’s unsettled. Land’s cheap. Few Indians left.”

“You thinking of moving there?”

“Dunno, will think about it.”

Jim Henry's father came to breakfast the next morning disheveled, dark circles under his eyes, and deep lines embedded from his ruddy cheeks to his mouth. He hadn’t slept.

Celia rushed to put a cup of coffee in front of him. “You all right? Heard you tossing most of the night.”

“Can’t see no other way. We’re moving to Iowa.”

With his father’s words, Jim Henry's idyllic life watching ants in the barn with Chester ended.

If felling and clearing trees were abominable to settlers, cutting through ten-foot tall blue stem buffalo grass, with tangled seven foot underground roots, to find black fertile soil was thrice as grueling. The heartiest of men succumbed in despair.

Word spread of the Hunt’s plan to move to Iowa. Their neighboring kin, the Windriff’s, whose corn suffered the same smut as the Hunt’s, were eager to join in the move to Iowa.

In the discussion on where to settle, once in Iowa, one of the older Windriff boys butted in. It must have been Moses who got the brilliant idea. An antitheses of Jim Henry, he was a bulwark young man, extruding a self-centered confidence, and impulsive to the point he felt the only way to solve an argument was a good fist fight. To be fair, everyone agreed Moses was the one to depend on "to carry the water over the hill" in tough times.

As if God were speaking, he pronounced, “It’s obvious. We’ll settle at the point where trees end and prairie begins.” For two families who seldom agreed on anything, Moses’ revelation struck a harmonious accord.

Best of both worlds, they agreed. Timber for building cabins and barns, and wide, unlimited expanses of fertile soil at their bidding. They’d have a sod crop in no time.

Their vision was clear. Blue sky above, rows of cornfields below, rain-soaked to spectacular lushness with each quarter turn of the moon. A land of milk and honey. Abraham’s promised land. Heaven on earth. In their glee and enthusiasm, none thought anything existed that would stop them. God’s blessing was with them. Onward!

Far away in the tumbling hills, the great and wise Chief Manitou, supreme Indian ruler and master of life, shook his head. Had he been present, he’d have raised his spear and tapped a solemn warning on the shoulders of the exuberant men. Neither family heretofore had broken an inch of true prairie sod, the likes of which they were about to encounter.

One fine cloudless day in October—settlers always began their migratory treks on fine, cloudless autumn days after harvesting their crops—two Hunt wagons, each drawn by a pair of sturdy oxen, and a similar entourage of Windriffs began their journey. They departed at dawn leaving Martin County and its devastating corn smut behind and welcoming a new land, freshly gold from wild oats turned by summer's scorching sun. With each wagon filled to capacity with small children, farming tools, and household wares, they trudged west along numerous creeks to Terre Haute expecting to find Indian trails winding north along the Wabash River.

On the first leg of their voyage west, the wagons logged twelve miles and settled peacefully for the night.

At sunrise the following day, as the men finished their morning coffee, Jim Henry's father called for the daily drawing. Doswell Hunt, dubbed Dozey by his father, drew the longest straw making his wagon the lead for the day. By agreement, the first wagon from the previous day was delegated to the rear, not unlike a Virginia reel where by dosey-do rotation each couple had the opportunity to lead.

Having bestowed upon himself the role of Captain and taking the lead wagon position yesterday, Moses was annoyed that his wagon today was at the ass end of the line. He shouted, “Pull to the right. Take the next turn along the river.”

“Damned if I will,” shouted Dozey, one hand on his rifle, the other grasping the reins of the oxen. “Any fool knows Indians travel on Indian trails.”

Immediately offended to be called a fool and looking for a diversion from the monotony of the tedious journey, Moses, followed by the Windriff men and boys deemed old enough to fight, jumped from the wagons, some rushing forward from tending the trailing livestock. Hunt defenders eagerly joined the melee. Face to face, they raised their fists and shouted epitaphs unfit for women folk. Moses threw the first punch, barely scraping Dozey’s head.

“River route, you asshole.”

“Hell no, you idiot. You want Indians to scalp us?”

“Watch who you call an idiot.” Moses' face turned the color of a red bird’s feather. His fisted knuckles remained white, not moving an inch from Dozey’s firm stance.

“I’m looking at him,” Dozey drawled, his sharp eyes penetrating the furious face of his cousin. He made a grand spectacle of looking around, left to right before shooting a smirking arrow straight to Moses. “Don’t see no others.”

Moses drew his arm back, his arm muscles bulging, to pummel his taunting cousin into oblivion. At that moment, Dozey’s brother, Johnny, jumped Moses from behind, the force of which sent both sprawling down a ravine. A free-for-all followed.

No longer facing his nemesis, Dozey jumped back in the wagon.

Whether to follow the wider, smoother trail where they might encounter marauding Indians, or a narrower path with heavy underbrush that no wagon or Indian was likely to travel was the issue. The sense and fists of the Windriffs were to take the wider, more travelable trail; the Hunts, considered by themselves to be more civilized and courageous, stayed adamant for following the more challenging and obscure route.

Wise enough to stay on his wagon while others continued to argue, Dozey took advantage of the circumstances and deliberately turned onto a narrow path where heavily encumbered trees bent together to form arches.

The second Hunt wagon, driven by Celia, followed. An oblivious Jim Henry, sitting next to the backboard near a coop of noisy chickens, calmly rubbed Chester behind his ear, measuring with his other thumb the distance between the tall cumulous clouds that seemed to follow their progress once they got underway from Martin County.

Not far behind, the Windriff wagons, driven by their women, faithfully followed like a string of obedient sheep following a tup over a cliff. Dozey’s lead wagon disappeared into deep shadows emanating from masses of inland river trees. The men, too angry to notice, were left in high animation pursuing their arguments. Creaking wheels and shouts from wives and daughters caught their attention, forcing them to run to catch the moving train.

Moses, smarting from his unfinished business with the fisticuffs, yelled from his position at the far end of the wagons, “Give me Liberty or give me Death.”

Dozey, grinning, triumphantly swirled his whip above his head before landing a blow on the rear of the slowest ox from which the ox responded with a quickening pace. “Cousin,” he taunted, “You ain’t the man to stop me.”

“You ain’t fair, Dozey. Wait til we camp. There’s more of us.”

“You mean more idiots. We’ll give you a fight, the likes of which you ain’t seen before.” Aiming to the sky, Dozey fired off his rifle, ruffling a flock of crows in the trees. Black, fluttering wings dispersed skyward wanting no part of the invading strangers.

Jim Henry heard his father chuckle under his breath, “Now, Dozey, you oughtta not treat your cousin that way.” His laugh turned to a guffaw. “He might get his feathers riled.”

Continuing around a curve in the trail, the advance of the wagons closed the matter, at least temporarily, from further discussion.

The heavy underbrush and overhanging trees required the heartiest of men and boys to switch from tending the herd of cows, pigs, and mares with foals, to cutting and clearing the trail ahead. Every backbone and hand was needed. All able men and boys were accounted for except Jim Henry who everybody long ago judged fit but too damn much of a mama's boy to do a man’s work.

“Jim Henry?” His father demanded, his patience gone, his irritation evident, his voice belching fire. “Where is that boy? Don’t he know his butt’s needed with the herd?”

Dozey pointed to the rear of his wagon. “Ridin’ like he was goin’ to church.”

“Ain’t church I have in mind. He’ll either tend stock or pray he has an ass to sit on when I get through with him.” His father cupped his hands and yelled louder, “Jim Henry, get yourself out here.”

Jim Henry heard the threats, but never argued, least of all with his hot-tempered father. Without answering, he roused Chester to follow, and slid from the back of Dozey’s wagon. On his way to the rear of the train, he gathered branches to swat any straying animal. Like-minded to the ambling cows and free spirited as the mares with their foals, he was content to be away from the cursing tempers and rowdy bustle of the wagons. Walking calmly among his charges, he stroked necks and patted rumps encouraging the herd to move forward. An aura of calmness permeated the woods. Birds sang and squirrels stood on their haunches watching them pass. He knew it would take two days to reach Danville, the jumping off place between the familiarity of the Indiana Territory and the wilderness known only as “the west.”

Danville was typical of a small town that had sprung from a few fur trading shacks and teepees to a crossroads with a general store, saloon, and stables.

Jim Henry, fetching prairie grass to the animals, heard his father speak to his brother euphorically as if he had found a great mother lode. “Moses won’t like it, but I think we ought to hitch up with those wagons down there. Clerk in the store says they’re going to Iowa. With their numbers, we’ll be safer.”

“Pa, you can’t be serious," Dozey protested. "Those wagons are Quakers. You don’t expect us to mix with war dodgers.”

“And why not? Cowards in war, maybe, but Indians don’t bother them. Don’t have to mix, just follow.”

“What makes you think they’ll want us behind them? You talked to any of them? They ain’t friendly to outsiders, you know.”

“Hell. Ain’t asking. It’s a free land.”

“Moses’ll think we’ve lost our minds. I agree.” He saw the ruddy face of his father turn the color of gray stone and knew the futility of arguing when his father’s mind was made up.

Subdued, Dozey asked, “Who’s telling Moses?”

“You are.”

Jim Henry threw down his armful of grass and stared at a group of wagons gathered at the bottom of the hill. He counted twenty which had formed a circular barrier around a mix of cows, oxen, riding horses, and hogs. He didn’t know what to make of the “Quakers” as Dozey called them.

Each wagon seemed to have its place. No one was idle. Tended by women and girls donned in gray dresses, white aprons and prayer caps, their fires sent billows of smoke aloft. Older girls stirred giant kettles hanging on iron crossbars across the flames. Girls his age carried babies in their arms, while mothers rushed back and forth between wagons and fires. Bearded men and boys no older than he, looked alike: tall black hats, collarless shirts, suspenders, and black trousers tucked into high, laced boots. Stern men inspected the wagon wheels and the feet of their oxen while barking orders to boys who scurried to find firewood and prairie hay. None argued nor appeared to carry fire arms. Quietly amused, Jim Henry found himself reminded of the ants he’d watched in the barn at home.

At dawn, the Quaker contingent organized their wagons, straightened the staging area back to nature's orderliness, and pulled methodically onto a trail heading opposite the rising sun. The Windriffs and Hunts, likewise, readied themselves to move forward. Dozey waited until the Quaker wagons advanced a hundred yards and then spread his arm wide motioning the remaining three wagons to fall in behind.

Crossing Illinois land of the famed Lewis and Clarke’s expedition, they found the country wild and thinly settled with Indians. Deer abounded plentifully as did quail, prairie chickens, wild turkeys, and wolves.

There was very little improvement on the few scattered farms: log cabins with no stable or any out buildings and only three or four acres of cleared land. It was in an untouched state, much like the Indiana Territory had been when his father and grandfather led settlers a generation ago to the edge of the frontier. It crossed Jim Henry's mind that each new generation seemed compelled to repeat their forefathers.

An advantage Jim Henry's father hadn’t mentioned was that following a larger train meant the Quakers were the ones who cleared the trail of fallen trees and brush, as well as determined which of the frequent sloughs near the creeks to cross and which to skirt around.

Sometimes the sight of cattails warned them of sloughs ahead, but more frequently than they wished, they mired in gumbo and were forced to take axes and chop sticky swamp clay from the wheels before proceeding. Very little sod had been turned on the land they crossed.

Ostracized by his brothers who didn’t think he was tough enough to wrangle stray cattle, Jim Henry walked ahead reporting back to Dozey whenever Quaker wagons did something different. On the second day of his new duties, he noticed the same Quaker boy lingered behind their livestock to make sure no strays straggled behind.

When the Quaker wagons stopped to survey a particular slough, which to Jim Henry appeared the size of a small lake, the Quaker boy sat on a downed, crosswise tree, whittling a stick to a point. Jim Henry saw the boy was not disturbed by his presence and took it upon himself to call, “Halloo.”

The Quaker boy silently tipped his hat in acknowledgement, but didn’t move away. A smaller boy with similarities that marked him a member of the same family, joined the boy on the log and pointed to Jim Henry.

Near enough to be heard, Jim Henry called, “What’s ahead?”

“Slough. A big one,” answered the older boy warily glancing at his visitor. He lowered his head and continued whittling, the chips swirling like fluttering leaves to the ground.

The younger boy shouted, “Who’re thee? Why ye following us?”

"Name's Jim Henry Hunt. Going the same place you are.”

Suspicious of the circumspect answer, the older boy asked, “and where be that?”

“Iowa.”

“Where in Iowa?”

Jim Henry shrugged his shoulders. “Don’t know. Where in Iowa are you headed?”

The boy put down his knife. “Don’t know.” He picked up his freshly pointed stick and laughed. “Cephas Ellis here. And that snoop is my brother Hiram.”

“Mind if I sit?”

Cephas shifted to make room. “It’s God’s log. Ain’t mine to say.”

Jim Henry asked, “Who are those people you’re traveling with?”

“Mostly Friends from Farmers Greenfield meetinghouse up north,” Cephas answered. “Ma has a wagon and we’re with Uncle Isaac.”

“Where’s your Pa?”

“Ain’t got one.”

“What happened?”

“Died three years ago. Ma’s new husband don’t want us and we don’t want him.”

An awkward silence ensued with Cephas clamming up, and Jim Henry sorry he’d asked.

Suddenly, Cephas’s face brightened. “Do thee go rattlesnake hunting?”

“Never have. Do you?”

“Yea, sloughs are full of dens. Counted thirty rattlers in the last one. Went around them, but can’t this time. Swamp’s bigger, but Uncle says we have to go through.”

Before Jim Henry could ask more questions about snakes, gunshots erupted from the Quaker wagons.

“Over here,” someone called.

“Vipers here.”

More gunshot.

More yells.

Twenty minutes passed riveted with a constant barrage of yells and gunfire.

Stunned, Jim Henry asked, “Why are they shooting? Indians?”

“No, not Indians,” Cephas’s voice was condescending as if the answer was evident as a bump on the nose. “Like I told thee. Rattlesnakes. Can’t move forward until we get them all.” He turned nonchalantly to his brother, “Come on Hiram, gotta go. Uncle will want us to pick them up.”

“Wait,” Jim Henry called. Only cows heard him. Cephas and his brother had disappeared into the herd.

Jim Henry's father gave a scurrilous eye to Moses. “Don’t you know anything? Indians don’t attack at night.”

“Then they’re hiding in the trees. Wait til morning.”

The trees looked ominous and Moses swore he saw Quaker shadows scouting the perimeter of their wagons. A cougar screamed, wolves howled. Children cried. Heavy waifs of smoke from the night fires of Quaker wagons streamed back to their wagons. Assisted by dark clouds hiding the moon, the night was fearsome and alive.

Jim Henry sensed phantom Indians were still lodged in Moses’ stubborn head in spite of evidence to the contrary. His cousin insisted, “You can believe what you want, but no one’s sleeping over there tonight. I tell you, we’re sitting ducks for an attack.”

His father’s confidence that Moses was blowing hot air wavered. “Dozey, go over and talk to their wagon captain. Tell him we’ll help fight when the Indians attack tomorrow.”

“Not me. They haven’t said aye, yes or no to us. You ain’t using common sense. They ain’t armed for Indians. Against Penn’s religion. They got to eat. Got to hunt.”

“Wrong. You heard the shots,” Moses argued. “They’re armed for an ambush.”

Despite his usual reticence to enter into an argument, Jim Henry couldn’t remain quiet any longer. Disgusted with the talk of Indians, he said with as much distain he could muster, “I already told you they were shooting rattlesnakes.”

Both camps quieted as the moon reemerged from the dissipating clouds and moved to its early morning position in the star-studded sky. A few scant hours later, the morning drill of fires, breakfast, and hitching completed, the Quakers moved out, slowly approaching the slough one wagon at a time. At the far side of the swamp, men on horses with ropes tied to the wagons and anchored around the trees, pulled to keep the heavy wagons from bottoming out and filling with backwater.

Mounting horses, Moses and Dozey crossed the swamp and prepared to do the same when it came time for the Hunt and Windriff wagons to cross.

While waiting, Cephas and Jim Henry found each other near a towering pile of mutilated snakes, the number being the point of mutual curiosity.

“How many do you think were shot?” Jim Henry asked, his admiration for his new friend growing.

“Don’t know. Counted easily 365 when I picked them up. Thee count them, if thee wish.”

With a perceptible intake of breath, he rushed to tell his mother. The snake dens had been in their path, no more than three hundred feet from the edge of their campsite.

To say the remainder of the trip to Iowa was uneventful would ignore the daily grind of keeping the wagons moving, grazing cattle, hunting small game, gathering brush and dried wood for stoking up fires at night, and settling arguments. Women busied themselves preparing food and keeping small children entertained. Few had time to knit or sew. Jim Henry's mother bantered that she wouldn't know what to do if there weren't at least one scrape, cough, or fever a day.

After a long discussion, with Moses claiming to differ, Jim Henry's father announced that tomorrow they would cross the Mississippi River into Iowa Territory. This knowledge came after Jim Henry told his father Cephas' uncle had said so.

"My map says different," Moses argued. "We have at least another day before we get to the low banks of the Mississippi."

"Do what you want, but the Hunts are crossing with the Quakers," his father countered. "Quakers know what they're doing. They don't lie."

Faced with a difficult forging, the two groups joined in a mutual effort to assist all the wagons across the perilous river. Working hand in hand, the differences between Jim Henry's father and Isaac Ellis became unimportant. He soon addressed his counterpart, Brother Isaac. Anyone looking for Jim Henry found him with Cephas. The boys were inseparable.

After two days of the most strenuous labor any had endured, the successful wagons gathered on the west side of the Mississippi, each man collapsing from exhaustion. None wanted to ever cross the river again.

Cephas took up whittling with Jim Henry sitting with him watching the wagons reassemble. Cephas was jubilant. "We're in Iowa."

"Can't tell by me. Ain't seeing no difference. Land, trees, and sky look the same."

"Guess I won't see you after tomorrow," Cephas said quietly, pretending not to notice the catch in his voice.

Engulfed with the sad reality of their journey together ended, Jim Henry solemnly agreed. "Probably not ever. At Skunk Creek, you're going east, we're going west."

Clarke County, Iowa. 1844.

A number of years later, Jim Henry and Moses settled old scores amicably and married Kilmore sisters, Eva and Zina. He and Eva struck out on their own settling on Otter Creek; by design, a sizeable distance from his father’s home place. Unlike his brothers, who lived near his father, he fended for himself—built a cabin and open-sided barn, raised livestock, and cleared a small portion of his forty acres.

Over the summer, by trading his labor with neighbors, he accumulated two milk cows and three hogs, but no oxen. A dower of three steers had been given to them by the Kilmore’s when he and Eva married. By his own brute force pulling a single plow blade, he'd managed to clear a two-acre corn patch and a small garden to satisfy Eva. His sod crop of corn had been meager, but he and Eva cut prairie grass with scythes for winter feeding and stacked it in tall mounds next to the open side of the barn.

When an unusually warm fall threatened to turn into a nasty winter, they agreed to sacrifice one shoat to provide meat until the snow banks melted and Jim Henry could hunt in earnest for wild turkeys, quail, and small game.

Having lived in Iowa, first on his father’s home place and now on his own, he thought he was accustomed to harsh winters. But this winter was a bear, worse than any previous one in memory with non-relenting blizzards, frigid weather, and high, ice-crusted snow banks. Water froze in a matter of minutes both outside and inside the cabin.

From the first day of December, their farm was snowed in leaving Jim Henry and Eva evenings for quiet contemplation, sharing of memories, and marveling the quick way night comes in the winter. Life took over and time trapped inside their cabin dragged on in a monotonous pattern. After supper, Jim Henry sat before the fire, smoked his pipe, and watched Eva mend shirts and socks.

So much had happened since they first came to Iowa. He remembered the Quaker wagons, Cephas Ellis and the snakes, and the emptiness for their lost friendship when the Quakers turned east to Jefferson County while they continued west to Clarke County. For the short time they'd known each other, they found much in common—a fondness for watching nature, a certain calmness within themselves, and a total dislike for arguments.

Jim Henry puffed short spurts of smoke from his pipe, his eyes reflecting a glaze back in time filled with memories. During the last three weeks of their trek to lower Iowa, he and Cephas had been soul mates although they often said nothing. Neither minded silence.

In quiet times when he seemed distant and lost in thought, he'd told Eva since striking out on his own, he'd felt the aloneness of his childhood when he and Chester had watched ants in the barn. He missed having a close friend.

“Eva, you didn’t know him, but I hope our paths cross with Cephas and his brother some day. They were Quakers, but we were great friends.”

Jim Henry recovered his aplomb. “At least we don’t worry about our Windriff cousins.” He paused picturing a certain memory, then chuckled. "After Moses argued it was his turn to take the lead, he drove his wagon into the slough without unloading one speck of the heavy gear.”

“Slough? What are you talking about?”

“The one with the rattlesnakes. You remember,” he gently remonstrated, “told you a million times about them.”

Catching up with Jim Henry's story which indeed she’d heard many times, she nodded at her grinning husband. “Why are you amused?”

“Providence, Eva. Providence. Their wagon tipped and took on smelly brackish water and would have sunk in the mire had not the Quakers come to their rescue with horses and ropes." Sobering at the thought of the disaster that could have happened, he sucked on his pipe pondering his thoughts but withholding his smile. "In spite of their good will, Moses huffed off and refused to thank them or admit he’d needed their help.”

“What happened to the Windriffs?”

“Wasn’t long before the Windriff women complained about the harshness of the land. They were scared."

Eva lifted her brow indicating her question hadn't been answered.

"Oh, sorry. Moses was never far from his rifle. He convinced them Indians would attack at any time."

"It was impossible for him to believe otherwise." Jim Henry continued, "I remember thinking I would explode if I heard one more time Moses complaining, "Now if we were in Indiana . . .."

Although he’d been sorry for the hard feelings, Jim Henry didn’t blame his father this time when his temper got the best of him. He remembered clearly his demand when they readied their wagons to cross the Mississippi, “If you don’t want to come with us to Iowa, go home.”

Jim Henry interrupted himself, lifted an ember and paused to relight his pipe. He inhaled through the stem. The ember showed no glow.

“Tell me more.” Eva prompted, biting off between her teeth a final thread from her darned sock. She replaced the needle in its cushion and set her sewing aside.

Jim Henry patiently repositioned the ember further into the bowl of his pipe and inhaled deeper with no better result. Returning to his thoughts, he responded, “They did.”

“Did what?”

“Went home.”

With his pipe stubbornly unlit, Jim Henry changed his mind about smoking and emptied the bowl of tobacco ash in the fireplace. Undressing to his long johns, he pulled a buffalo robe over him making room for Eva to join him. “I’m freezing. Too cold for stories tonight.”

From his memories of long ago, what he realized he hadn't forgotten were the struggles that ensued between his father and him--he for recognition of his worthiness, his father for control. Now as an adult, buried deep in nature's frozen earth, he knew that although their differences would always keep them apart, he was ready to forgive and forget. He reached his arm around Eva and whispered, "Ain't nothing going to stop us. We'll make it."

Each morning Jim Henry fought through new snow to chip ice in the troughs and pitch prairie hay for his stock. Every night he shoveled corn, only a scoop or two, into the trough and put out hay. His bin of shucked corn was almost empty. If storms continued, he wondered what he would do when he had no more. His father’s dire warning came back like a cloudburst of rain: Without corn, humans and stock starve. He felt helpless. Worse, nature made it impossible to gather seed pods and acorns buried under the snow for hog mash.

One particularly icy night, he found one of his steers the Kilmore’s had given him missing. The gate was ajar and tracks led from the barn to the snow-covered stubble cornfield. Grabbing an axe and rope, Jim Henry followed the tracks to the edge of the field, and beyond the three fence posts still visible above the wind-blown drifts, he saw a young buffalo calf snarled neck deep and thrashing with no hope of freeing himself. A few feet away, his wayward steer struggled to stay atop the drift. With the glare of snow and ice shimmering from the backs of the animals, he almost missed seeing them. Plaintive calls from the frozen animals caught his attention.

Taking his axe, Jim Henry cut a path through the drift and lassoed one end of the rope to the buffalo calf and the other end to his steer. He placed himself in the middle position of the rope, pulled forward, and called to his steer, “Joey, come on, boy.”

Recognizing the calm voice that brought him to the barn each night, Joey edged forward tromping deep footprints in the snow.

“Come on, Joey,” he begged softly. “Just a little more. You can bring your friend.”

Joey took two steps and halted when the bison pulled back with a rebellious cry that sounded as if a volcano had traveled from his rump, through his stomach, to his throat. Jim Henry, holding his temper in check, continued to coax the steer, pulling gently on the rope. Finally, Joey proceeded slowly following Jim Henry through the cut in the bank of snow. The bison followed, first hesitantly, then lock step with Joey.

Back in the barn, Jim Henry put his steer in the same stall with the other two steers and reached to move the bison into the newly vacated space. The bison balked, jerked his head, and plunged his body forward missing by inches his unwanted tormenter. Temporarily frozen in shock, Jim Henry's legs numbed, his shoulders shook in fear. Almost feeling the gore, he wiped his brow. His heart's palpitations told him, "Close call. Should've known better."

The berserk bison bellowed and stomped his feet, head down, the hair on his spine rigidly barbed, his back arched to repeat his charge.

Joey sounded an answering call.

The bison paused, deterred for only a moment, before butting his head forward. Sensing immediate danger of a second nasty gore, Jim Henry jumped quickly to the top of the stall. The bison hit the side with such force, Jim Henry toppled into the next stall.

Joey called, this time unmistakably yearning for his new friend. Once again the bison stopped.

“Okay, Joey,” Jim Henry said picking himself up and opening the stall gate with his foot. “Who’s your friend? Come on, boy, guess there’s room for the two of you.”

“What are you talking about?” Eva scolded, a lantern in hand. “Was worried what took you so long. I was on my way to find you.”

“That steer you insisted naming Joey was missing and when I found him, he was tangled up with a bison calf in a snow drift. The steer wouldn’t come without the bison, and when I got them to the barn, the bison wouldn’t calm down until I put Joey with him. Did you ever hear anything so strange?”

“A bison in a stall? Aren’t they too wild for that?”

“Eva, he’s as big as the steer, but only a calf. Not sure how he got into our field. With five foot drifts, I guess he could’ve walked right over the fence.”

Eva nodded. “Makes sense with snow covering their forage, buffalo would drift closer to us. But a cow wouldn’t leave her calf. No mother would. You thinking the calf was lost or worse, his mother killed?”

Jim Henry lowered his head, his eyes wincing at the thought, and nodded sadly. “Wolves howl both day and night. Winter’s a killer. Everything wild is hungry.”

The following day, Jim Henry paced the floor, looking out the window every hour hoping the blizzard had eased. "If it isn't new snow, it's the damn wind blowing drifts over where I shoveled yesterday." He had tried to worry quietly to not upset Eva, but he had seen the bottom of the corn bin and counted the days until it would be empty. He continued to pace.

"Can't you find something to do besides worry? I know it seems futile to try to keep a path open to the barn." She touched his shoulder, "Think of spring, by March, this’ll be over.”

“That’s only part of the point. Two acres won’t be enough. Have to find some way to plow more prairie.” He rubbed his back and groaned. “I can't do it myself without oxen.”

“Talk to the Bakkers, maybe Jake will loan you his oxen for a week.”

“Ain’t likely. Has his own plowing to do. They got the same snow we did."

Jim Henry bundled up, buttoning his heavy coat and pulling down the flaps of his cap to cover his ears. He squeezed his large hands into gloves, the tips worn through exposing his fingers to the bitter cold. "Time to shovel again. Cows to milk.”

Eva stood by the door ready to push it shut once Jim Henry braved the gusty wind to leave. “Don’t worry, you’ll think of something. You always do.”

Entering the barn, he found the buffalo calf was up to old tricks. He bellowed, charged the gate, and reared back with his hind legs daring Jim Henry to come closer. It was obvious, only the presence of Joey kept him from tearing the stall apart. “You ungrateful son-of-a-gun, I ought to put you out in the cold and see what you think then.”

Joey called. The buffalo calf stopped kicking but defiantly shook his head back and forth. Jim Henry stepped out of the way and pondered his new challenge, studying the calf from all directions. With edgy nervousness, he began to observe what was in the calf's mind and what tormented his soul. The buffalo was a hell of a lot bigger than the ants in his father’s barn, but since it was too early to do anything in the fields, he decided to tame the buffalo to behave in the stall and not go into a frenzy when he came each morning.

Forced to carry on a conversation with himself, he missed Chester. First of all, the buffalo needed a name.

Bill, came to mind. Short and sweet. A liberated buffalo. Damn shitter doesn’t warrant a family name and certainly no relative, even Moses, would want to be associated with such a beast.

He continued musing his options, focusing on regaining his patience with animals. “Okay, Bill it is. Joey and Bill.” He reached over and rubbed Joey’s flank. “That all right with you, Joey?”

He dipped into the bin and pulled out an ear of corn, shelling off a few kernels. Joey nuzzled the palm of his hand for the corn. “See, Bill, Joey’s a gentleman.”

He shelled a few more kernels and took a step towards Bill. The buffalo shook violently and butted against the side of the stall, his hind legs splayed like a bronco.

“Whoa! No call for that.” Jim Henry backed away, jumping quickly to the top of the stall. "More time you need, is it?"

“Okay, Bill, don’t have enough corn for you anyway. Have it your way.” He was about to stalk away when he looked into the buffalo’s terrified eyes. “Why, Bill, you ain’t mean, you’re scared.”

Bill edged over to Joey and rubbed his nose between Joey’s hind legs. Jim Henry laughed, “He ain’t got nothing for you. Shoulda known. You’re a baby who wants his mama.”

He continued to sit a safe distance from Bill. After ten minutes, when Bill seemed calmer, he inched over closer humming a tune that had no words. With visible tremors, Bill took notice, snorted, but didn’t move. Another ten minutes, inches closer, Jim Henry kept up his humming and soothing banter. “Atta boy. Ain’t no one’s gonna hurt you.” When he was within reach, he leaned over to touch the buffalo on his neck. Manifesting his terror, Bill jerked, arching his back.

“Okay, okay. Ain’t ready yet. Enough for today.”